A couple of months ago I looked at various build systems in the hopes of finding an ideal one for C++ development. In particular, the most important criteria I was using was iteration time for incremental builds. Jam was the clear winner and things looked good.

Fast-forward a few months and one aborted attempt at implementing that build system, and there are now more unanswered questions than answers. It turns out that Jam and its successors were far from the perfect solution I had envisioned, so I was back to square one. I took this opportunity to look into all the build systems I had left out of the first article, plus all the ones that other people asked me about since then, to come up with a much more comprehensive evaluation.

The Contenders

Jam

Since Jam is the culprit that caused this second go-around, I figured I would start with it. What’s wrong with Jam? Isn’t it the fastest kid on the block? It still is the fastest, but when it comes to supporting new platforms or adding new settings to builds, it’s not the most straightforward of all systems.

Jam is a bit too complex for my tastes. Even after sitting for a while with the Jam tutorial (which is a horrible introduction, by the way), reading the skimpy documentation many times, and playing around with some sample Jam files, it was still very difficult to create non-trivial Jam files. At that point, my best allies were the Jambase and Jamrules files themselves. When it came time to start adding support for features such as precompiled headers, different build configurations, or Xbox 360 support, things got a lot harder very quickly.

Jam is a bit of a puzzle. Out of the “box” it claims to be able to have platform-independent Jam files, and that’s the source of the problem, because it makes it a lot harder to support new platforms. In my case, since I’m targeting a very specific set of platforms, I would much rather specify each build rule myself and have a simple, clean set, instead of a monster set of rules that applies to everything.

At the same time, Jam doesn’t support some really basic features, such as spaces in filenames. Not like I advocate having spaces in filenames, mind you, but that’s an unfortunate reality of the setup of many Windows computers. Yes, I know I can patch it, but this is where the next, and biggest, problem of Jam comes in.

Jam is dead.

Yes, Jam is completely dead. The Jamming mailing list has less traffic than a side road in Siberia during the winter. My attempts at asking there for help went completely unanswered (except for one kind soul who emailed me privately, apparently too embarrassed to post to a dead mailing list).

The fact that the latest official version of Jam dates back to 2002 should have been a good tipoff, but somehow I didn’t catch on to that at first. The nail in the coffin was when I asked where the latest set of patches, or the latest unofficial version of Jam, was located and nobody, *nobody*, answered.

So where is everybody who developed and used Jam? Oh, they must have gone to one of Jam’s successors, like BoostBuild. That’s good, right? Right?…

BoostBuild v2

BoostBuild v2 is promising on paper. It builds on top of Jam to add several much-needed features such as multiple configurations, correct filename parsing, etc. Or at least so it seems.

As soon as I start digging into it it’s very clear that BoostBuild is much more complex than Jam. It’s not like Jam was a walk in the park, but BoostBuild is close to unacceptable. I’ll take a Makefile any day of the week. Still, I would be willing to overlook that, bury myself deep in the documentation, and learn the system inside out if BoostBuild lived up to expectations: Jam speed with more features.

Unfortunately it doesn’t. It doesn’t just fall short either, it misses by several miles and destroys a friendly nearby town in the process. BoostBuild was the slowest of all the build systems I tested. Slower even than Scons! Talk about taking something small and fast and turning it into a slow, lumbering beast.

On the up side, I won’t have to spend months learning the overly complex system. I had to find a silver lining somewhere, right?

Is BoostBuild v1 any better? It could be. But frankly, after my experience with v2 I wasn’t in the mood to go check it out. Besides, it sounds like they’re going to phase it out. If I want a fast, dead build system, I’ll choose plain Jam.

Microsoft Visual Studio 2005

I had heard (from the comments in the previous articles and other posts on the internet) that Visual Studio 2005 had an improved build system. Even though it seems that C++ is getting the shaft and not being rolled in the MSBuild system for this release, apparently it was still improved somewhat. Since a beta version of Visual Studio 2005 fell in my lap at the GameFest conference earlier this year, I decided to give it a try.

I had heard (from the comments in the previous articles and other posts on the internet) that Visual Studio 2005 had an improved build system. Even though it seems that C++ is getting the shaft and not being rolled in the MSBuild system for this release, apparently it was still improved somewhat. Since a beta version of Visual Studio 2005 fell in my lap at the GameFest conference earlier this year, I decided to give it a try.

Incremental build times were definitely improved, although they are still far from Jam times. The one-second delay for each project is reduced to a bit less than half a second. Better for sure, but I don’t see why it can’t be faster. Still, that’s getting in the range of being more usable.

One interesting addition is that, by default, Visual Studio 2005 will use multiple threads to compile C++ code. That will be a very welcome addition for full builds. Now I really need a quad-processor machine for our build server.

VCBuild

MSBuild, the Ant clone that Microsoft has been hailing as the next great thing to come, doesn’t yet support C++ builds. It’s a matter of priorities, I suppose. In the meanwhile, MSBuild will use the standalone VCBuild tool to compile Visual Studio solutions.

VCBuild promises to be a lightweight, command-line version of devenv.com, ideally suited for build servers. Indeed, VCBuild had slightly better build times than MSVC2005, which is a huge improvement over 2003. That actually puts VCBuild as the fastest build system after Jam and Make.

At this point, I was interested enough to think about starting to use VCBuild for all of our command-line builds (at the server and the quick verification build before submitting code). Unfortunately, I immediately ran into a couple of problems. The first one is clearly listed in the Readme, so I knew it was coming: VCBuild will not add a dependent project to the link list like MSVC does. This is actually a good thing. I always hated that dependencies implied linking in Visual Studio. Unfortunately, since that’s the default behavior, we are relying on it 🙁 It’s easy to change, but it’s just one small obstacle in the way.

The more serious problem was that VCBuild didn’t seem to parse all the project settings correctly (warning levels for example), so it created very different results than a build with devenv.com.

Finally, I was disappointed to see that VCBuild does not support multiple processors. I had started thinking of VCBuild as a standalone MSVC2005 project compiler, but that’s clearly not the case.

Fast Solution Build MSVC plugin

This one isn’t really a standalone build system like the others covered in this article. However, it directly addresses the problem of speeding up Visual Studio builds, so it was worth including it in. In the past, I had very mixed experiences with it, but after hearing some really good things about it from some co-workers, I decided to give it a whirl.

As promised, Fast Solution Build does speed up incremental Visual Studio builds to speeds similar to Visual C++ 6.0. That is to say, doing an incremental build with no changes on a large solution takes about a second, which is really how it should be. This time around, I didn’t have any problems with strangely broken builds or anything, so it seems pretty stable.

Unfortunately, Fast Solution Build is not without its set of problems. The first few problems are relatively minor. It doesn’t seem to play well at all with C#. If I ever make the mistake of attempting a fast build on a C# project, Visual Studio will start a build and never end. The only way to get out of that state is to kill the process and restart Visual Studio. I guess I just need to train my fingers not to press F7 in C# projects.

The other problem is more of a user problem than anything related to the plugin. In spite of its name, Fast Solution Build, it does not build a solution, but it builds the selected project. That alone caused more problems than anything because most people are used to doing solution builds, not project builds. It’s especially problematic if you want to have several unrelated projects build simultaneously (like in the case of unit tests projects and a game executable in addition to the libraries they depend on). More than once, we ended up checking in code that seemed to build fine, but broke when the server built the full solution.

The lack of a command-line interface also kills Fast Solution Build as a long-term solution. It might be OK while you’re working with the IDE, but you can’t use it for any command-line builds such as in the build server or for a quick sanity check we have before committing any code.

However, the biggest problem of all with Fast Solution Build is that it’s just a plugin to Visual Studio, so you’re left with many of the problems in Visual Studio itself, such as being hard to set up large solutions with lots of dependencies, having the visual representation mixed in with the real dependencies, suspect dependency checking (try deleting a file and then doing a build), or being tied to a single platform.

All in all, if you want a quick fix to your build times, Fast Solution Build is a good temporary band-aid provided you don’t work with C# much and you don’t have very complex solutions.

Scons

As I was wrapping up the new measurements, I noticed the announcement in for the new version Scons (0.96.91 pre-release). Since the last version was many moons ago, and since there was talk about improving Scons’ performance, I decided to give it a try.

The new version is indeed faster, but only by a tiny amount. Scons still lags far, far behind the curve in terms of performance. Unless the developers manage to squeeze performance improvements of several orders of magnitude, it’ll remain unusable as a build system for fast iterations.

Ant

Ant is one of the build systems I consciously left out of my first roundup. I had used it a bit in a build server, but I had the impression it was mostly intended as a “build sequencer,” with high-level actions like archiving files or emailing, and intended for full, nightly builds, rather for fast C++ incremental builds. It turns out that even though Ant was developed primarily with Java development in mind, it does have C++ support through some of the extra contribution tasks, with full dependency checking.

Ant is one of the build systems I consciously left out of my first roundup. I had used it a bit in a build server, but I had the impression it was mostly intended as a “build sequencer,” with high-level actions like archiving files or emailing, and intended for full, nightly builds, rather for fast C++ incremental builds. It turns out that even though Ant was developed primarily with Java development in mind, it does have C++ support through some of the extra contribution tasks, with full dependency checking.

Another fact that put me off a bit from trying Ant was its level of verbosity. Writing XML files is anything but fun, and I much prefer the terseness of a Make file than the verbosity of an Ant file. Still, if a tool does the job well, I’ll put up with a lot.

Ant’s dependency checking was not bad, but not great either. Incremental build times with Ant were a bit worse then MSVS2005, but not by much. Frankly, that’s faster than I expected with my initial preconceptions.

Full build times on Windows were blazingly fast. So much so, that I was convinced I had configured something wrong and I was only doing half the build. It turns out that everything was fine, but Ant will send all cpp files to be compiled to the compiler at once, whereas other build systems will process them one at a time. Under Linux with gcc, this doesn’t make much of a difference, but in Windows using the MSVC compiler, it makes a huge difference. Other build systems should take note of that and take batching much more seriously.

Nant

Nant is Ant’s evil twin written with the .Net framework instead of Java. Frankly, I don’t really see the point of Nant when Ant is already a mature project and runs in many more platforms. To make matters worse, the Nant developers decided to make their syntax different from Ant. Was that really necessary? If at least it were a straight Ant clone, it would be easier to migrate from one to the other. Personally, I would have preferred to see all that energy put into improving Ant instead of creating a .Net clone.

Having said that, one of the early surprises of Nant was its native support for C++ compilation. In Ant it was a custom task, here it works out of the box.

Nant also has a good set of extra contributed tasks, including support for Perforce operations (although for a lot of the operations I wanted to do, I ended up having to fall back to command-line scripts because the tasks didn’t have enough parameters or support for exactly what I wanted to do).

Another potentially interesting feature of Nant is support for Visual Studio solution files. This could be very useful because it would move the dependency checking out of Visual Studio and into Nant. Unfortunately, I tried running it on the solutions at work and it failed miserably. It seems that lots of compiler options are not parsed correctly, so it was impossible to build our existing solutions. I also suspect that C++ isn’t their main target, so C++ project support is probably lagging behind C# and Visual Basic. Although I didn’t try it, I imagine that Nant would choke at trying to build an Xbox 360 solution file.

Just for kicks, I tried running it on Linux with Mono, but apparently it only works with the Microsoft cl.exe compiler, not with gcc.

Build times were almost identical to those of Ant. Nant does very good batching as well, so full builds were blazingly fast, but incremental builds were only middle-of-the-road.

Rake/Rant

I don’t do any Ruby development, so I had never heard of Rake until Ivan-Assen Ivanov told me about it. In for a penny, in for a pound, so I went ahead and ran the tests on Rake as well.

Rake is a build system written in Ruby (and I assume mostly intended for Ruby users as well). Like Scons, it brings the full power and expressiveness of a scripting language (Ruby in this case) to the build script. It looks pretty simple and clean. The Ruby syntax is a bit strange at first sight, but it’s easy to get used to (especially with lots of examples).

Unfortunately, Rake doesn’t have C++ dependency checking built in. I could have probably cobbled something together with makedepend, but that would take more Ruby-foo than I’m comfortable with.

Of course, all of this being open source, somebody, somewhere has had the same itch to scratch, and Rant was born. Apart from the cool name (after all, who doesn’t like to write Rantfiles?), Rant looks very similar to Rake. Don’t be fooled by their parallels to Make and [N]Ant. It’s much more Make meets Scons in Rubyland than a derivative of Ant.

One feature of Rant that I really liked was the good support for error messages. If the Rantfile had a problem in it, it would correctly identify the problem and point me to it. After working with Ant/Nant, that was a welcome change.

The build times were a bit of a mixed bag. Full incremental builds were pretty good, definitely in the top third of the build systems I looked at. Unfortunately, building a single library without any changes was extremely slow. It seems that Rant had to do a lot of work before it could even look at an individual library. If it weren’t because of that, I would be a lot more excited about it.

Make and MSVC2003

Nothing new in this front. For details, just read the first article. Everything there still applies.

The Method

I used the same test case and hardware as the last time. As a quick recap, the source code was made up of 50 static libraries with 100 classes each (2 files per class), 15 includes per cpp file to other files in that library, and 5 includes to files in other libraries.

The Python script generates a tree with a full code base for every build system along with all the necessary build files. Whenever the build files for two platforms are different, two separate trees are created. Thanks to Jim Tilander to writing the Python scripts to generate the BoostBuild files.

The computer was a P4 2.8GHz CPU with 1GB of RAM and a 7200 rpm hard drive. The Linux distro was Mandrake Linux 10.2 with the 2.6 kernel and Windows XP (without any antivirus running–which makes a huge difference!).

The Results

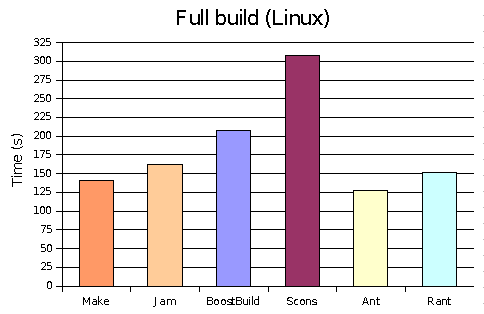

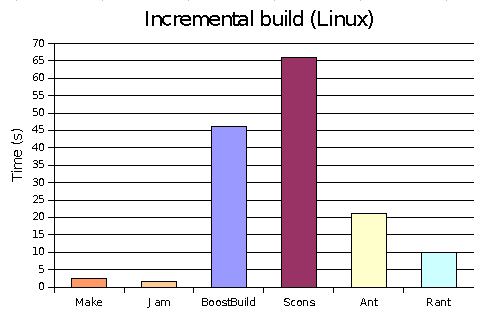

Linux with gcc 3.4.1

| Build system | Full build | Incremental | Incremental lib |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNU Make (3.80) | 2m 21s | 0m 2.4s | 0m 0.0s |

| Jam (2.5) | 2m 42s | 0m 1.6s | 0m 0.1s |

| BoostBuild v2 (3.1.10) | 3m 28s | 0m 46s | 0m 1.6s |

| Scons (0.96.91 pre-release) | 5m 08s | 1m 06s | 0m 10.4s |

| Ant (1.6.5) | 2m 8s | 0m 21s | 0m 1.7s |

| Rant (0.4.4) | 2m 32s | 0m 10s | 0m 4.9s |

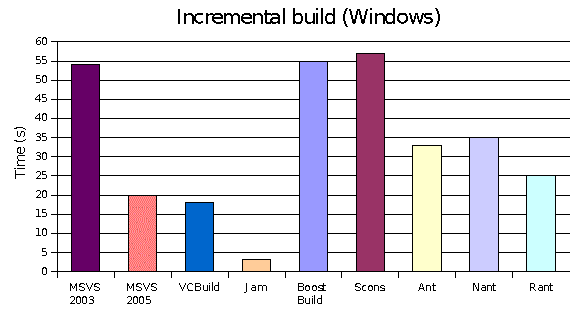

Windows XP with MSVC 2003 compiler (except for the MSVC2005 run).

| Build system | Full build | Incremental | Incremental lib |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microsoft Visual Studio 2003 | 7m 28s | 0m 54s | 0m 4s |

| Microsoft Visual Studio 2003 + FastSolutionBuild | 7m 26s | 0m 1s | 0m 1s |

| Microsoft Visual Studio 2005 | 6m 46s | 0m 20s | 0m 3.5s |

| VCBuild (7.10.3088.1) | 6m 56s | 0m 18s | 0m 0.5s |

| Jam (2.5) | 6m 52s | 0m 3.1s | 0m 0.3s |

| BoostBuild v2 (3.1.10) | 12m 03s | 0m 55s | 0m 2s |

| Scons (0.96.91 pre-release) | 7m 52s | 0m 57s | 0m 7s |

| Ant (1.6.5) | 3m 42s | 0m 33s | 0m 1.9s |

| Nant (0.85) | 3m 24s | 0m 35s | 0m 1.4s |

| Rant (0.4.4) | 5m 47s | 0m 25s | 0m 14s |

Update: Since several people asked, I timed Scons with MD5 checksum checking turned off in the hopes of getting a better time. I followed the advice described here. Just like last time, turning off MD5 checksum made it go slower if that makes any sense.

| Scons build (Linux) | Incremental build time | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 1m 06s | — |

| –max-drift=1 | 1m 10s | +5s |

| –implicit-deps-unchanged | 0m 47s | -19s |

| –max-drift=1 –implicit-deps-unchanged | 0m 50s | -16s |

Using the option to indicate unchanged dependencies made it go a bit faster, but that’s not an option we can realistically use during development, since that would be changing constantly with the structure of our program. Still, the fact that without doing any dependency checking it’s still taking 47 seconds. What is it doing??

With multiprocessor machines being so common these days, a good build system needs to support parallel execution of tasks in multiple processors. Surprisingly, not all of the build systems compared here support it. Of the usable build systems, only Make, Jam, and MSVC2005 actually support parallel builds.

| Build system | Multiprocess builds |

|---|---|

| GNU Make | Yes |

| Microsoft Visual Studio 2003 | No |

| Microsoft Visual Studio 2005 | Yes |

| VCBuild | No |

| Jam | Yes |

| BoostBuild v2 | Yes |

| Scons | Yes |

| Ant | No |

| Nant | No |

| Rant | No |

Conclusion

Jam still remains the best-performing build system of all by quite a lot. Unfortunately, the total lack of support and community around it make it very difficult to recommend. There has been some talk recently in the sweng-gamedev mailing list to do some work for build systems. Maybe we could take over the continued development of Jam. If that happened, I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it. Until then, unless you’re a Jam expert or are willing to dig through user-created patches in the Perforce Public Depot, Jam is not a realistic option.

MSVS2005 has improved a lot from 2003, and along with VCBuild, it’s one of the best performing build systems under Windows for incremental links. Personally, I hate to be locked in to proprietary tools and single platforms, so I would opt for the next best systems, which are Ant/Nant. Pick your flavor of choice, they’re about the same.

MSBuild can be promising, especially once Microsoft rolls out their XNA Studio extensions specifically designed for asset building. It’ll only run in Windows, but at least they claimed that they’re making it general enough you can use for building any type of assets, not just their own formats. That’s definitely one to watch for the future.

If you’re comfortable with Make files, it still remains as a great option for very fast builds. You’ll probably want to wrap Make in a more comprehensive build system (such as Ant) for your build server, packaging builds, etc. But Make can be your everyday workhorse during development.

Whatever you do, stay far, far away from BoostBuild and Scons. Their performance is simply so horrible there’s no excuse to use them unless build times are of no importance to you at all.

I remain hopeful that we might be able to resurrect Jam. If you’re interested in contributing, contact me through email, comments on this page, or participate in the sweng-gamedev discussion directly

Thanks for the hard work on the roundup. Can you add cmake http://www.cmake.org/ to the roundup?

Thanks for great article but I have a question about SCons. This system has several flags that may speed up builds significantly. Did you try them?

(the flags I am talking about are for disabling MD5 checksums and caching implicit dependencies)

Alexey,

Yes, I did try those flags in my previous article. I too was hoping they would cause a big speed up, but they didn’t make much of a difference at all. I didn’t get around to trying them with the pre-release version of Scons though. Let me know what results you get if you get a chance to try them though.

IncrediBuild has had good results for our team. They have a trial version you can use to try it out, but it’s best used when you have a fair number of machines to pull from. http://www.xoreax.com

Don’t get me started with Incredibuild again 🙂 http://www.gamesfromwithin.com/articles/0502/000069.html

The strangest thing I ever saw was where, at a former job, a full rebuild of the project took about 15 minutes with Incredibuild, when there were 10-12 hosts helping the build, and the same build on only my dual hyperthreaded processor machine took only 7 if I used jam -j6.

I wouldn’t be too harsh in telling people to avoid BoostBuild due to performance. A lot of work is going into developing and finetuning BBv2 (it hasn’t officially been released yet, BBv1 is currently the build system being used by Boost, but should be phased out in the next Boost release). The current CVS version of BJam/BBv2 and the upcoming M11 release have significant improvements over M10 in both features and speed.

At the moment, the documentation is still in its early stages but is getting better and is one area they are focusing on. Aside from that, the mailing list is active with very talented people willing to answer your problems. In fact, the BJam/BB mailing list may have superceeded the Jam mailing list :).

In terms of cross-platform development, BoostBuild is definitely the way to go. However, if rebuild times is a priority, use the CVS version or wait for its release.

I don’t think it’s of any use to Noel, but Electric Cloud is an interesting product in this space. If you are stuck with a gigantic set of recursive makefiles, this tool looks good. It essentially nullifies the penalties for having a recursive make by sharing information between successive calls to make. It’s an interesting idea, which is very similar to Rational’s Clearmake.

Electric Cloud hasn’t been worth it for us.

How come no mention of a make under Windows?

Nice blog talking about build system

I know you are going for quickest edit-compile-run times, but I think there are two competing things in cross-platform builds.

[1] making dependencies fast

[2] using the best available dev environment for a given platform.

I’ll talk about [2] first.

I used to believe that the best idea for cross-platform development was to create some sort of master build script that kicked out builds for all of your various platforms.

Then the company I work at did just that. It was a nightmare to get up and running. It is mostly working now, but it is STILL under active development. It went from a small little side project to a very large ongoing project for this poor guy.

It would be awesome if it just worked, but there always ends up being little exceptions here an there. Soon your master build file ends up being a complex monster.

Here is what I currently believe:

You have platform specific code, so have platform specific builds!!

Yes it is more work to create and maintain a build for each platform, but as long as you follow two rules, it really is not bad.

1. No dead files allowed.

2. Platform specific code goes in its own directory.

The idea is basically to use a script for each build that generates the build using wildcards.

There are details along with a vc7 generator script in my blog. I’ve since created a more elaborate vc71 script, if you want it, mail me.

http://projectjanel.org/b2e_blogs/index.php?blog=2&title=cross_platform_build_systems&more=1&c=1&tb=1&pb=1

Back to [1]. Nothing I’ve said goes against it. You just make the choice of the best dev environment for each and every platform. So if you want to have a vc6 AND vc7 builds for win32 because one of your guys refuses to switch, fine. If you want to use gnu make on linux because it works well there, fine.

The main idea is just not to try and shove all those builds into a single magic build. All that ends up giving you is the lowest common denominator.

Noel,

I’d like to see your SCons results using timestamps rather than md5 hashes for the files. I suspect that would bring SCons times down a fair amount.

Cheers,

Barry.

Very interesting articles!!

I am planning a build system upgrade for my team.

I did not get the following statement:

“You’ll probably want to wrap Make in a more comprehensive build system (such as Ant) for your build server, packaging builds, etc. ”

Are you describing a design where you have 2 different build systems operating on the same code base?

How would you design such a system without a too high maintenance cost?

How would you teach your developers (let say a team of 10) to modify the source tree organization (add files, directories, etc) and keep the two systems in sync?

Okay, enough with the questions 🙂 Thanks for the great work!

Jean,

When I said that about Make, I was thinking of a fairly clean division along the lines of just building the executable with Make, and leaving any other tasks such as zipping it up, creating install programs, copying it over the network, checking it/out of version control, etc in Nant. The Nant script would of course call the Make as part of its work.

I would see the Nant script being used primarely in the build server, and maybe by individual developers in the rare case they need to do some of those tasks by hand.

Barry, I updated the results section with timings of Scons with the MD5 checking turned off. Just like last time, it actually went slower. Hard to believe, I know. The script is there though, so feel free to run both and compare.

Hi Noel

You might be interested in checking out the following url:

http://www.martinfowler.com/articles/rake.html

“Whatever you do, stay far, far away from BoostBuild and Scons. Their performance is simply so horrible there’s no excuse to use them unless build times are of no importance to you at all.”

Hey, you’re talking only about performance. I don’t think it’s the only important factor when choosing a build system.

While SCons might be slower, it might still save you a lot of time :

– You don’t have to write complexe makefiles, but instead can write much more simple SCons scripts.

– You don’t waste time on a not-working build because some file was not recompiled while it should have been

SCons does a lot more than a simple Makefile. If use an external tools to add features like automatic implicit dependencies to you makefile, I’m not sure SCons is much more slower.

Two other interesting articles on the same subject :

http://freshmeat.net/articles/view/1702/

http://freshmeat.net/articles/view/1715/

Visual Studio 2005 (just released) ships with a new version of VCBuild which supports parallel builds and has a whole new set of options.

This MSDN page lists some (but strangly, not all) of the command line options:

http://msdn2.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cz553aa1

I’d say switch to jvm platform. By using java or scala you get great build systems (ant, maven, gradle) and other tools, IDE, libraries, super fast memory management, variable escape analysis (so it’s allocated either on stack or heap), hot code swapping, quick startups that doesn’t require long compilation, simple reflection and much more. Parts that are most memory/performance critical may be written in C++ and later called through Java Native Interface, sockets, ZeroMq or any other mechanism.